Public Participation Geographic Information Systems: using mapping to empower local communities

Maps, and satellite-based maps in particular, are not only cartographic tools, but can become empowering instruments enabling collaborative decision-making.

This concept is at the core of Participatory GIS or Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGIS). This expression refers to a participatory approach to spatial planning aimed at sharing spatial information and communications among people who share an interest on certain places and assets.

The term was coined in 1996 at the meetings of the National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis in the US. The approach includes several techniques for mapping and knowledge exchange (from ground mapping to participatory interpretation of remote sensing images), involving local communities and empowering them to co-build, use and share geo-spatial information and maps.

IRMCo (Integrated Resources Management) is an environmental research company based in Malta that uses the PPGIS approach since its creation in the early Nineties. We have interviewed the founders of the company, Anna Spiteri and Dirk De Ketelaere, to know more about this approach and better understand its added-value to concretely transfer the benefits of space-based information to local communities.

IRMCo (Integrated Resources Management) is an environmental research company based in Malta that uses the PPGIS approach since its creation in the early Nineties. We have interviewed the founders of the company, Anna Spiteri and Dirk De Ketelaere, to know more about this approach and better understand its added-value to concretely transfer the benefits of space-based information to local communities.

“Adopting a spatial perspective helps to identify, understand and address issues of spatial relationships of land ownership and use on the ground, and approach spatial conflicts with a different perspective.” Anna Spiteri and Dirk De Ketelaere

To understand how this approach is applied in practice, Anna and Dirk told us about two projects in which IRMCo implemented public participatory geographic information systems. The first is SIRIUS (Sustainable Irrigation water management and River-basin governance: Implementing User-driven Services), an FP7 project which ran between 2010 and 2013. The project aimed at developing efficient water resource management services in support of food production in water-scarce environments, with case studies in Spain, Italy, Romania, Turkey, Egypt, Mexico, Brazil, and India.

In such countries, water scarcity can result, especially in summer, in water crisis, causing different sectors to compete for water use. Since agriculture is globally responsible for 70% of water use, the SIRIUS project aimed at using data from European satellites (from the Copernicus constellation, at the time called GMES) to assess irrigation water requirements, taking into account the interrelated economic, environmental, technical, social and political dimensions of the food-water challenge. While the intended users of the project were public water authorities, farmers were its main beneficiaries.

Within the project, IRMCo worked with farmers and stakeholder organisations to motivate them to optimise irrigation water use in their communities using geospatial information as the basis for knowledge sharing and dispute resolution. With the support of “local champions” (people reputed and respected within the targeted communities) Anna and Dirk gathered local stakeholders and asked them to look at printed satellite images of their fields to capture local knowledge on agriculture and water resources and visualise how they could reintroduce traditional irrigation practices that proved to be equitable and inclusive in the past.

As an example, in the Nile Delta, in Egypt, the communities living around the Sefsafa and Daqalt canals were complaining about inequalities in water distribution following the construction of the Aswan Dam (an enormous engineering work realised between 1960 and 1970 that even implied the relocation of several archaeological sites). Some farmers complained that the pumping activities upstream left very little water available to the farmers downstream, and particularly at the tail end of the same irrigation canal.

After recalling how irrigation was managed before the construction of the dam, the farmers, who would have had difficulties working on a digital map, drew on the printed satellite-based map a fair and equitable way to pump and distribute irrigation water in the area. The discussion resulted in a set of recommendations to resolve their conflicts, an impressive result for a community that does not have a farmers’ association to talk over collective interests like it happens in countries like Turkey or Spain.

Always within the framework of the SIRIUS project, Dirk and Anna worked with the government water authority of Forquilha, a municipality with a Mediterranean, arid weather in the north-east of Brazil. Here, farmers living upstream and downstream of the dam had a conflict about irrigation water use. Also, in this case, they were gathered around a printed satellite-based map of the area and asked to recall their irrigation practices before the construction of the dam. Based on their recommendations, the government water authority was able to identify a better place for the dam, which was then relocated in a period of only six months.

“It is amazing how farmers, who generally lack IT skills, are immediately able to locate their farms on the printed satellite-based map and to make concrete suggestions on how to improve their irrigation system”, Dirk told us.

Irrigation management is only one among the many topics that can be visualised and explored by looking at a satellite imagery in a participatory fashion. On a smaller scale, the satellite-based map of a city or of a neighbourhood can reveal plenty of information that remains invisible to our eyes while walking in the streets.

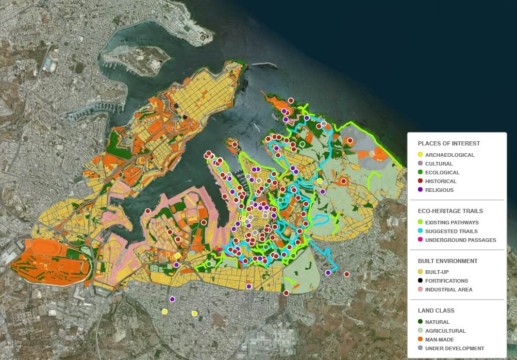

In Malta, where Dirk and Anna have been living for most of their lives, IRMCo used the Public Participatory GIS approach to empower local residents to safeguard green and blue open spaces in the southern part of the Grand Harbour area. Here, the open spaces were mapped using satellite-based data that was then verified with ground surveys. This experience was made possible thanks to the Mare Nostrum project (Bridging the policy-implementation gap in Integrated Coastal Zone Management across the Mediterranean Sea Basin), a cross-border project funded by the European Union under the ENPI CBCMED Programme.

The project, implemented between 2013 and 2016, aimed at exploring new ways of protecting the Mediterranean coastline, bringing together 11 partners from Malta, Greece, Israel, Jordan and Spain, including leading research institutes, local municipalities, SMEs, environmental NGOs and port operators.

Valletta’s Grand Harbour is a natural harbour that has been substantially modified over the years. The Grand Harbour was the base for the Order of Saint John for 268 years and its fortifications resisted the Ottoman forces trying to conquer Malta in 1551 and 1565. Used since prehistoric times, the Grand Harbour hosts a number of archaeological remains and historical buildings of great cultural interest.

Today, the Grand Harbour is a densely populated and built area, where open spaces are quickly disappearing. Within the Mare Nostrum project, each open space was recorded on a digital map through field mapping and classified according to its accessibility, conditions and other variables. In a period of three years, Dirk and Anna organised ten workshops with local residents and stakeholders, including the mayors of six municipalities of the areas, businesses, local administrations, historians, and university researchers concerned with urban planning.

The community was invited to contribute with its knowledge on the archaeological, cultural, historical, green and religious sites of the area and was then asked to draw on satellite-based maps on a digital tablet to connect the sites of interest through heritage trails that would pass through the remaining open spaces, thus highlighting their importance.

The goal of the project was to bring more tourists to the Grand Harbour while also safeguarding open spaces in the area.

Local community draws suggested eco-heritage trails in Grand Harbour (Source: http://www.grandharbourcharter.net/)

Indeed, the residents of the Grand Harbour were complaining about overdevelopment and pressure on open spaces and their lack of empowerment vis-a-vis the local powerful construction industry.

The application of the PPGIS approach in the Grand Harbour represented the first ever application of crowdsourcing in Malta. The field surveys resulted in a wide range of GIS maps characterising open spaces, which are freely available online: www.grandharbourcharter.net

The maps provided the basis to organise a series of seminars during which participants produced a “Local Communities’ Charter for Liveable Cultural Landscapes in Malta’s Grand Harbour, A Place for Our Children”. The Charter is also available on the project website for people to sign up to it.

The satellite-based web maps allow anyone to outsource local knowledge of places of cultural and ecological value through online drawing of eco-heritage trails. Moreover, the maps represent a powerful tool to bring the voices of the residents to the decision-makers in Malta. Indeed, residents use these maps to contrast building projects in the area and have become a reference for them.

The results of the project in Malta and the Local Communities’ Charter for Liveable Cultural Landscapes in Malta’s Grand Harbour, “A Place for Our Children”, was launched during a media event in the presence of the Minister for Social Dialogue, Consumer Affairs and Civil Liberties, Helena Dalli, and was signed by the representatives of Local Councils and NGOs and by numerous residents. The results of the project also caught the attention of a number of associations and media and were the object of a documentary that was broadcast by Television Malta.

“Communities are usually willing to participate in mapping processes if their purpose and outcomes are clear. Therefore, and not least to avoid creating false expectations, it is necessary to be very precise about the whole process from the beginning and explain that: the participatory mapping process is aimed at achieving benefits for the community as a whole; the project’s research activities are geared to collect the local communities’ views on coastal planning and management in their environment; and that the outcomes of the process may be used to influence policies and practices so that communities’ views are taken into account in decision making”. Anna Spiteri and Dirk De Ketelaere

Currently, IRMCo has an ongoing project, AQUACYCLE, which brings together six partners from Greece, Lebanon, Malta, Spain and Tunisia, and in which they are engaging local communities in the drawing up of domestic wastewater reuse action plans. The ambition of the project, which is funded under the ENI CBC Med Programme, is to bring about a much-needed paradigm shift in how wastewater is perceived as a waste rather than as a precious resource in its own right.

The project’s eco-innovative wastewater treatment technology is aimed at bringing a low-cost wastewater treatment solution, particularly to relatively small-sized farming communities around the Mediterranean, who are faced with an unsure future due to the impact of climate change on already scarce water resources. Pilot demonstration sites of the wastewater treatment technology are foreseen in Lebanon, Spain and Tunisia.

Public Participatory GIS might be the approach so much needed to finally bring the benefits of satellite-based information to local communities, offering people a concrete means to sustain their rights, perceptions and opinions towards public administrations. In this sense, this approach could represent the Holy Grail for the appropriation of satellite knowledge and technologies by local communities. We are looking forward to seeing PPGIS becoming a common practice, to be integrated in all projects aimed at developing operational satellite-based services.