Messages to the above: Looking at art from the sky

Eurisy just released its first article on the theme “Space for Arts”

What’s the interest of realising an artwork that can only be appreciated in its entireness from the sky? Apparently, none. Nevertheless, giant artworks perceivable only from above have been realised since the most ancient times, while the history of architecture counts endless examples of sophisticated buildings, castles, gardens and the like, which plan or iconography can be only seen clearly by watching at them downward from above.

Examples of land art, integrated in natural or urban landscapes, continue generating interest also in the XXI Century, responding to what seems to be a peculiar human need for “decorating” our planet, while showing off our idea of beauty to those who might be watching from above.

This article wants to provide our readers with a short introduction on how aerial photography and satellite imagery have changed our way of looking at the Earth, inspiring art movements and allowing for the discovery and appreciation of ancient and more recent artworks, be them nature-made or man-made.

The origins of aerial photography and its influence on arts

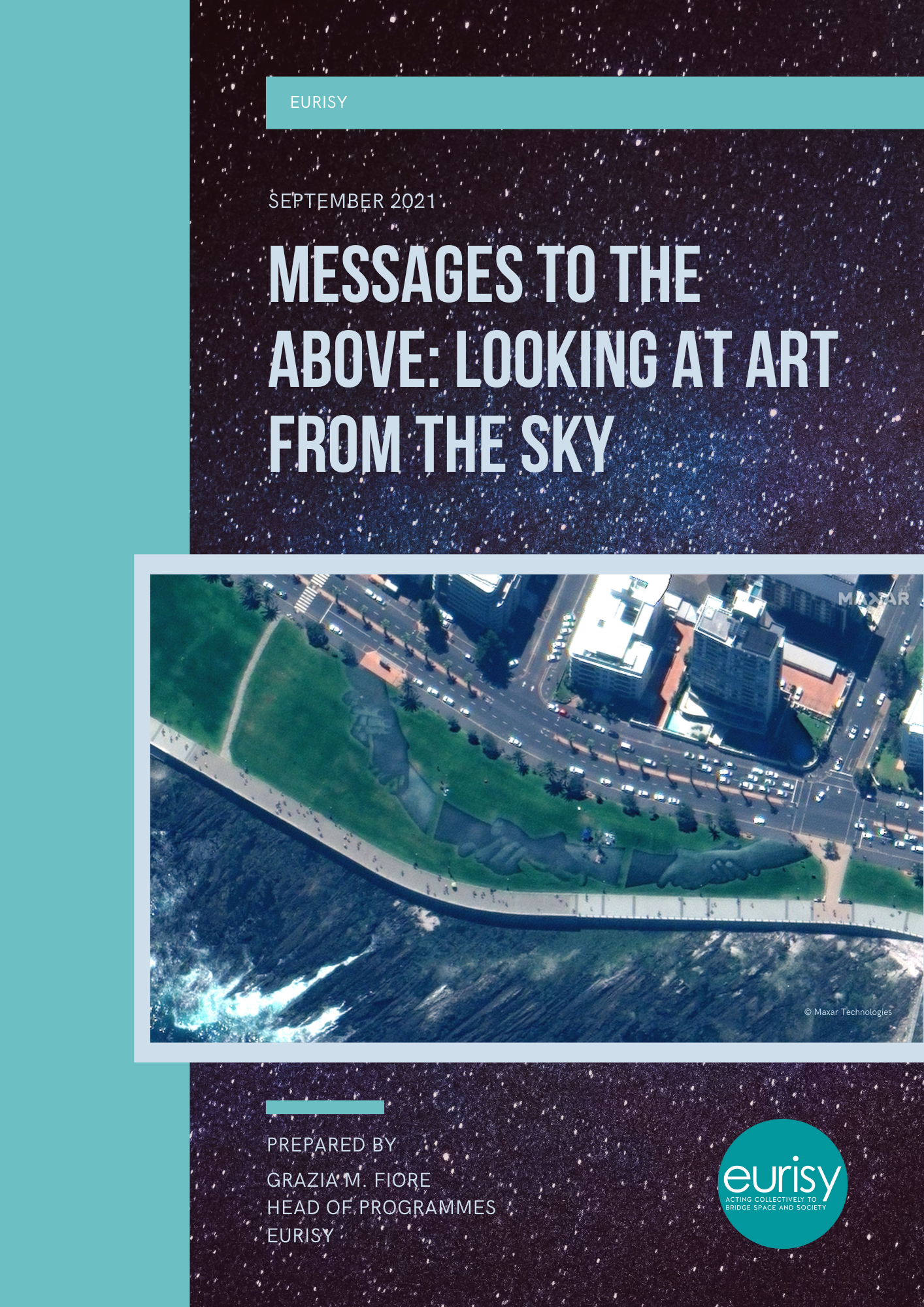

The first aerial picture we recall was taken by the French photographer Nadar in 1858 from a tethered balloon at 500m from the ground. This first snap of Paris seen from above is today lost, but it inspired a number of contemporaries to follow suit, the most known being James Wallace Black, whose picture of Boston taken from a hot-air balloon represents the first clear aerial photograph of a city.

These pictures unveil to the public a new iconography, allowing for the discovery of a flattened Earth. “The Earth unrolls in a huge carpet without edges, without beginning or end”, Nadar wrote.

This panoramic view of the landscape inspired photographs, filmmakers, painters and architects to experiment with the possibilities offered by perspective: the images change depending on whether they are observed from far or from near, from above or from below, while the horizon line gradually disappears.

During World War I, hundreds of aerial pictures are taken from airplanes for military purposes. By changing the perspective of the viewer, these photographs will affect the work of contemporary artists, from the Bauhaus movement to Paul Klee’s oblique or perpendicular landscapes, to Jackson Pollock’s all-over paintings, realised by throwing colours on canvas laying on the ground and reminding the aerial pictures of bombs released from airplanes during WWI and WWII.

The power of abstraction of what is called “bird’s-eye view” is particularly evident in the paintings of Sam Francis, illustrating the memories of his two tours around the globe as a pilot in the late Fifties.

Aerial photography and archaeology

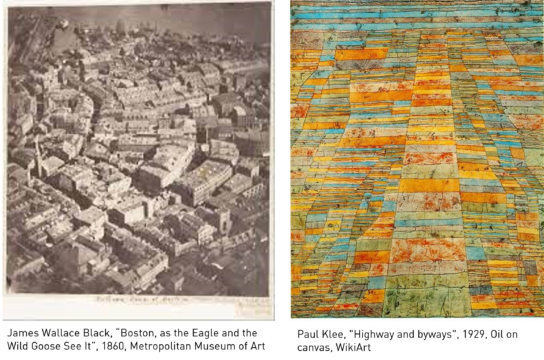

In addition to influencing artists, progresses in aerial photography also represented a precious tool for natural and human sciences. Indeed, Paul Kosok, credited as the first researcher of the Nazca Lines in Peru, first acknowledged their existence thanks to aerial photographs of the sites in 1939.

Forty years later, the American photographer Marilyn Christine Bridges was able to capture the whole of the site from a plane, delivering to the world the first artistic snaps of the largest existing concentration of earth drawings.

The Nazca Lines are a group of very large geoglyphs in the Nazca Desert in Peru, created between 500 BC and 500 AD by making incisions in the soil. Numerous scientists have studied the Nazca geoglyphs, also using satellite imagery of the sites, in an effort to understand the purpose of these giant drawings, conceived as to be seen from the sky.

Despite the technologies available, and the numerous theories proposed by the scientists who researched the Nazca lines – claiming that the lines were messages to the gods, astronomical representations, or even ceremonial paths – their meaning still remains mysterious.

The Nazca lines are not the only example of giant representations that can be only seen from above. Hill figures (large visual representations made by cutting into a steep hillside and revealing the underlying geology), have been created since prehistoric times and include human and animal forms, as well as more abstract figures.

Satellite imagery and archaeology

Satellite imagery has proved to be a powerful tool for archaeologists.

It allows scientist to identify new sites, even when these are buried underground, thanks to crop marks; in combination with ground measurements and spatial analytics tools, satellite imagery also allows archaeologists to identify physical interactions between archaeological deposits and the surrounding soil; moreover, satellite Earth observation facilitates the detection and monitoring of threats to heritage, such as deforestation, climate change, agriculture and urban sprawl, among others; finally, it can be the only available means to acquire information on the status of cultural heritage during conflict or emergency situations.

To know more about the uses of satellite imagery to study, monitor and safeguard cultural heritage, please read the conclusions of the Eurisy conference “Space for Culture” held in Matera (Italy) in 2018.

Arts, Land Art and Satellite Imagery: Science or Art?

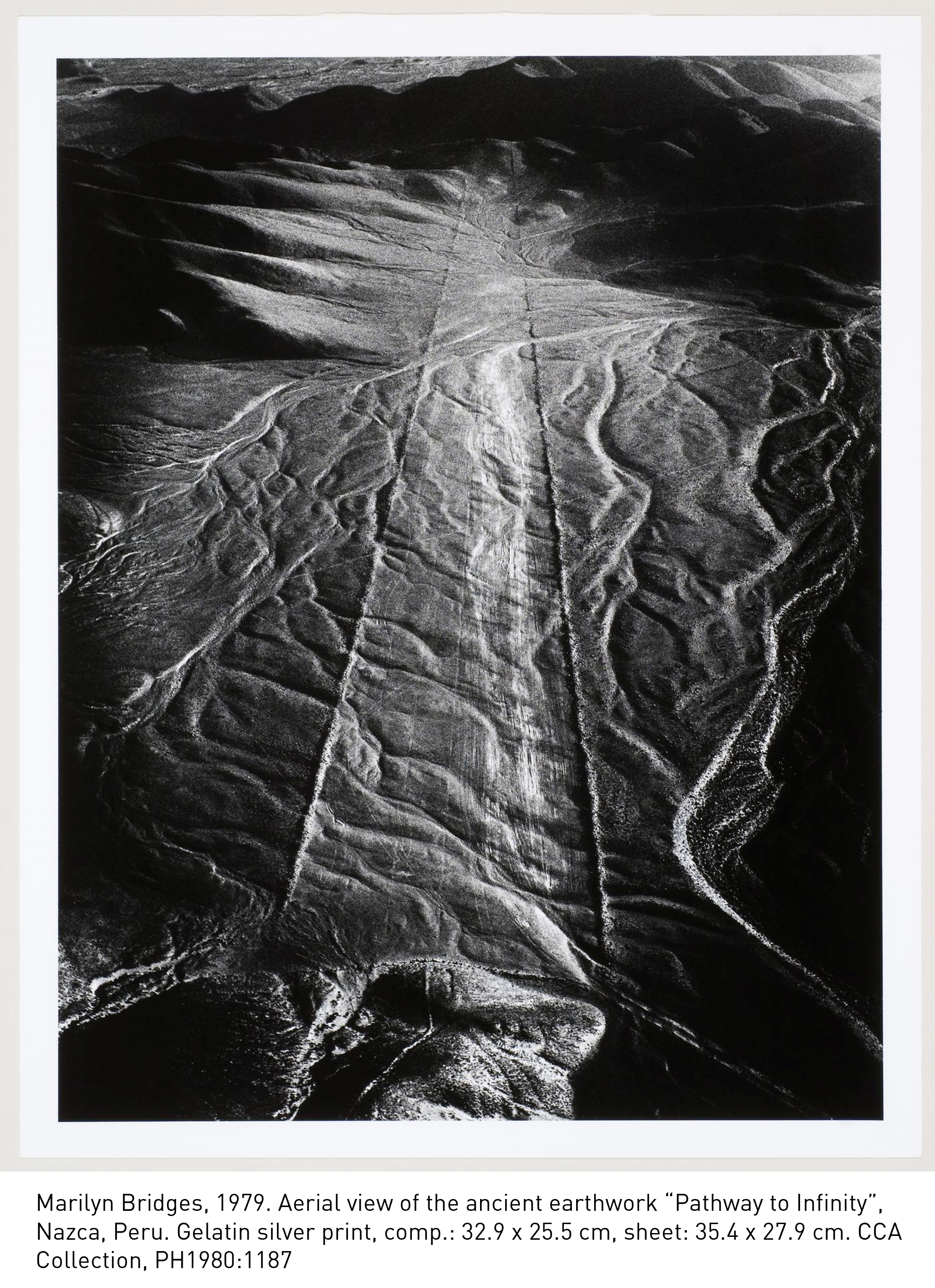

At the end of the 1960s, the pictures made available by aerial archaeology influenced and became a reference for the artists of the emerging Land Art movement.

Aiming at extending the reach of arts to the topographic space, this movement included the creation of very large artistic works, embedded in the surrounding landscape.

The movement was started by Robert Smithson and Dennis Oppenheim and includes among its representatives Christo Vladimirov Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (both known as Christo), and Alberto Burri, among many others.

The materials used within the Land Art movement were generally the materials of the Earth found on-site, while the location of the artworks was often inaccessible.

This means (and this is what interests us the most here), that the only way for the public to see and appreciate such artworks in their entirety was often through an aerial photography showcased in a gallery or by media.

Today, the deployment of satellites equipped with sensors with an increasingly high definition allows us to also perceive such artworks from the outer space.

If the quality of the images collected by satellites is not comparable with those of aerial pictures, the fact that such artworks can be seen from space carries an undeniable fascination.

Indeed, satellites add a new perspective to land art, inviting the eventual viewer to get closer to the art piece.

If the United States are the country with the highest concentration of Land Art works, some interesting examples of this movement can be also found elsewhere.

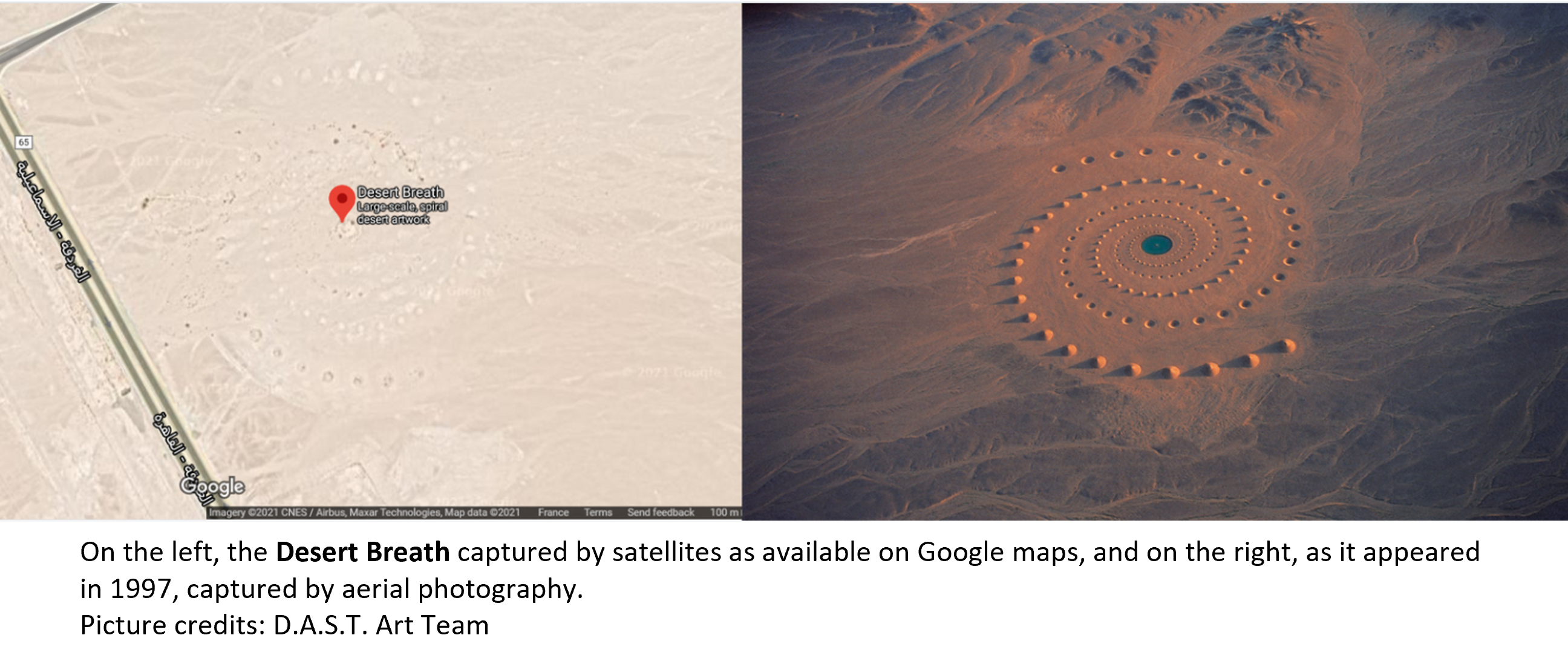

As an example, Desert Breath is an installation excavated in the sand of the desert in Egypt, nearby the Red Sea, by the D.A.S.T. Arteam collective between 1995 and 1997.

For this artwork, the artists used about 8 thousand cubic meters of material, 89 sand cones and 89 holes spiralled around a basin, on an extension of about 100 thousand square meters.

If the water in the tank has evaporated, the cones and depressions are incredibly still in their place, unchanging over time and still visible even from satellites.

What is the value of the images of Land Art from satellites?

Given the fact that they do not allow the viewer to fully enjoy the aesthetic features of these works, can we still talk about art? Or are we in the realm of science only?

An answer to this question can be partially drawn from the current master of global cartography, Google.

Indeed, Google Earth offers today a portal dedicated to Land Art. Merging satellite and aerial views, the portal showcases 10 modern examples of Land Art, coupling Earth views with descriptions of the artworks.

By combining art and cartography, Google erases the distinction between art and sciences, showing how the two domains can go hand in hand and support each other.

If since the end of the XIX century telescopic observations showed us that the space world can be assimilated to an artwork, the world seen from the space is not far behind.

Want to know more? Read the full article here